An End of Life Doula Approach to Accessing Palliative Care in Aotearoa New Zealand (Poster Presentation)

Last week I posted on Facebook about an opportunity for people to add their voices to New Zealand's Palliative Care Strategy. I have to admit that even for me, it is hard to sit down and actually submit something that I hope will be useful and valuable. Motivation can also be hard to find when there have been so many years of consultation in so many areas of our lives that never seem to make a difference, it is easy to wonder what is the point? I am usually a pretty optimistic person, so I am digging deep, reconnecting with my passion and my why and reminding myself that I am one of many drips in a pond that will eventually find its tipping point to become a wave, not just a ripple.

I have also spent a crazy number of hours this year working on some assignments that I'm actually pretty proud of. I figure it is silly to spend so much time on them for only the markers to see and then be hidden in files on my laptop forever more. These assignments have the potential to inform, educate and most importantly change how people access and experience palliative care. So I am pulling up my big girls pants and offering them to the world! Pretty exciting...

Here's a poster presentation I did. This is it in its entirety, but over the next wee while I will choose a section and take a deeper dive with you here in these reflections as well as on Facebook. My hope is that somewhere in this, you will learn something new, see something from a different perspective, find a new understanding, or simply feel a little more comfortable and able to share conversation with those you love about how you want to live fully all the way to the end.

(Note: This poster is designed to be printed in at least A3. If you are looking at this on a device, try to save the picture and then zoom in to read in full or below is the text from the poster that also features the graphics).

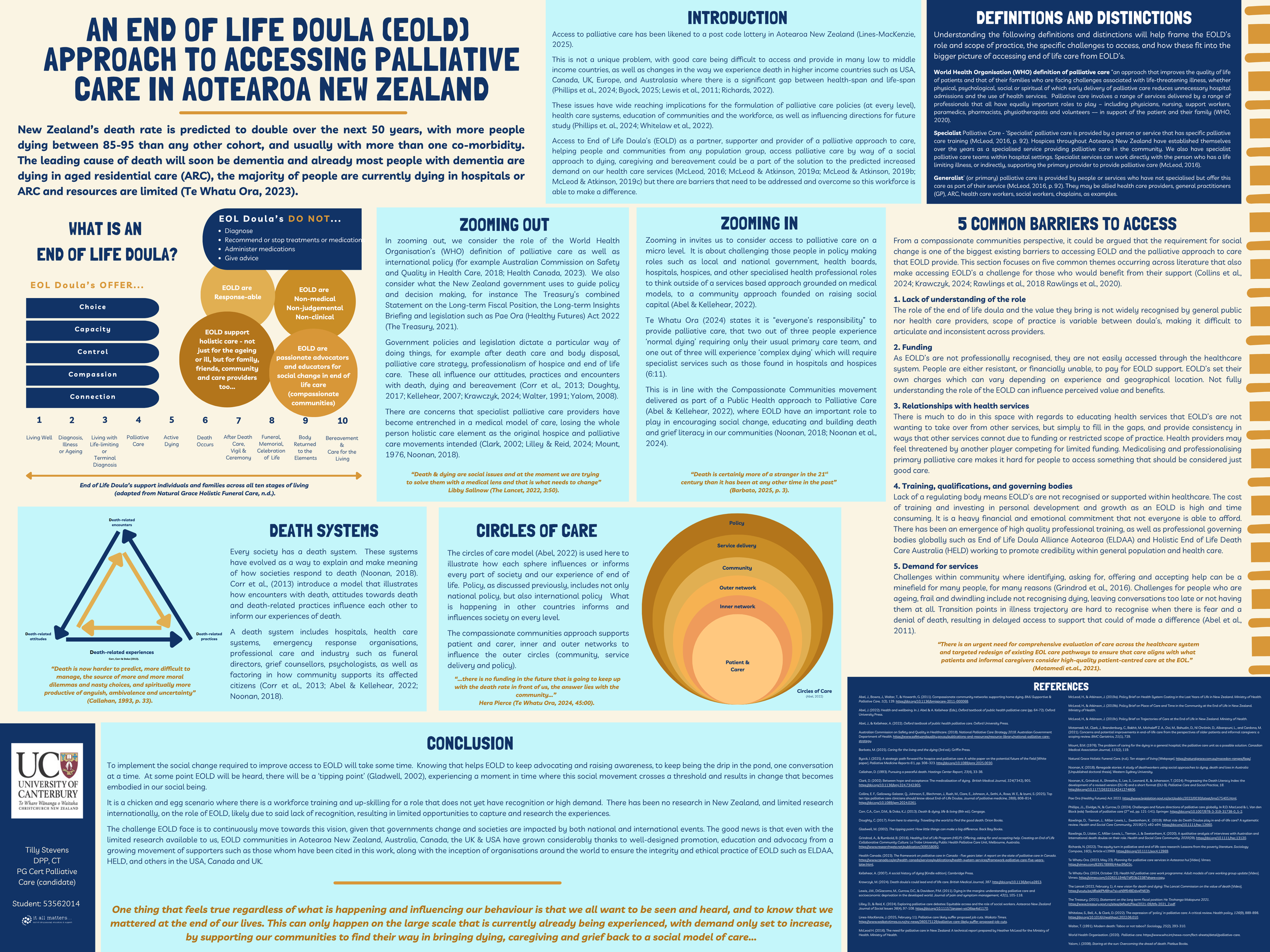

AN END OF LIFE DOULA (EOLD) APPROACH TO ACCESSING PALLIATIVE CARE IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND

by Tilly Stevens DPP, CT, PG Cert Palliative Care (candidate)

New Zealand’s death rate is predicted to double over the next 50 years, with more people dying between 85-95 than any other cohort, and usually with more than one co-morbidity. The leading cause of death will soon be dementia and already most people with dementia are dying in aged residential care (ARC), the majority of people are currently dying in hospitals or ARC and resources are limited (Te Whatu Ora, 2023).

Introduction

Access to palliative care has been likened to a post code lottery in Aotearoa New Zealand (Lines-MacKenzie, 2025).

This is not a unique problem, with good care being difficult to access and provide in many low to middle income countries, as well as changes in the way we experience death in higher income countries such as USA, Canada, UK, Europe, and Australasia where there is a significant gap between health-span and life-span (Phillips et al., 2024; Byock, 2025; Lewis et al., 2011; Richards, 2022).

These issues have wide reaching implications for the formulation of palliative care policies (at every level), health care systems, education of communities and the workforce, as well as influencing directions for future study (Phillips et. al., 2024; Whitelaw et al., 2022).

Access to End of Life Doula’s (EOLD) as a partner, supporter and provider of a palliative approach to care, helping people and communities from any population group, access palliative care by way of a social approach to dying, caregiving and bereavement could be a part of the solution to the predicted increased demand on our health care services (McLeod, 2016; McLeod & Atkinson, 2019a; McLeod & Atkinson, 2019b; McLeod & Atkinson, 2019c) but there are barriers that need to be addressed and overcome so this workforce is able to make a difference.

Definitions and distinctions

Understanding the following definitions and distinctions will help frame the EOLD’s role and scope of practice, the specific challenges to access, and how these fit into the bigger picture of accessing end of life care from EOLD’s.

World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of palliative care “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and that of their families who are facing challenges associated with life-threatening illness, whether physical, psychological, social or spiritual of which early delivery of palliative care reduces unnecessary hospital admissions and the use of health services. Palliative care involves a range of services delivered by a range of professionals that all have equally important roles to play – including physicians, nursing, support workers, paramedics, pharmacists, physiotherapists and volunteers –– in support of the patient and their family (WHO, 2020).

Specialist Palliative Care - ‘Specialist’ palliative care is provided by a person or service that has specific palliative care training (McLeod, 2016, p. 92). Hospices throughout Aotearoa New Zealand have established themselves over the years as a specialised service providing palliative care in the community. We also have specialist palliative care teams within hospital settings. Specialist services can work directly with the person who has a life limiting illness, or indirectly, supporting the primary provider to provide palliative care (McLeod, 2016).

Generalist’ (or primary) palliative care is provided by people or services who have not specialised but offer this care as part of their service (McLeod, 2016, p. 92). They may be allied health care providers, general practitioners (GP), ARC, health care workers, social workers, chaplains, as examples.

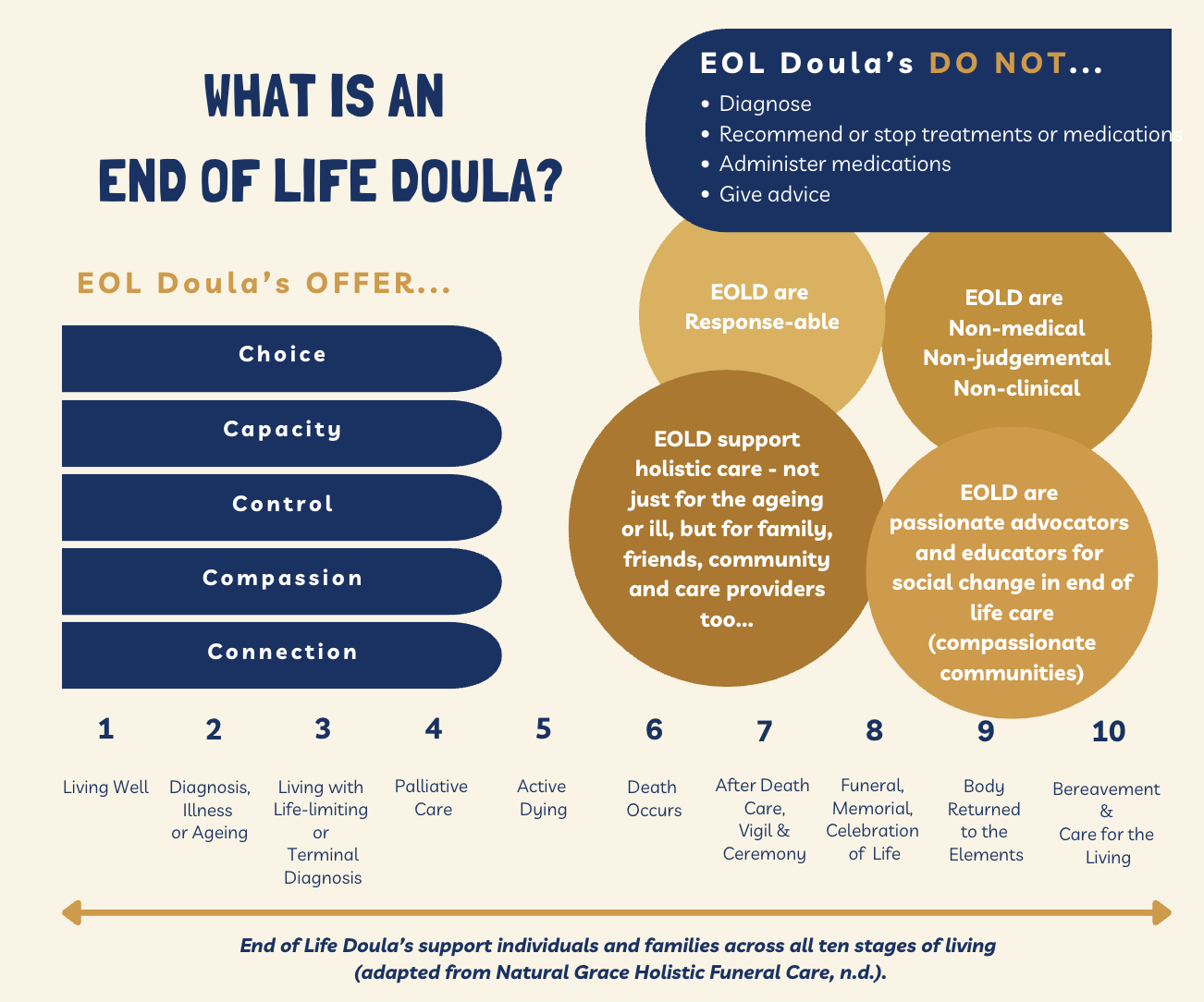

What is an End of Life Doula?

Zooming out

In zooming out, we consider the role of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) definition of palliative care as well as international policy (for example Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, 2018; Health Canada, 2023). We also consider what the New Zealand government uses to guide policy and decision making, for instance The Treasury’s combined Statement on the Long-term Fiscal Position, the Long-term Insights Briefing and legislation such as Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022 (The Treasury, 2021).

Government policies and legislation dictate a particular way of doing things, for example after death care and body disposal, palliative care strategy, professionalism of hospice and end of life care. These all influence our attitudes, practices and encounters with death, dying and bereavement (Corr et al., 2013; Doughty, 2017; Kellehear, 2007; Krawczyk, 2024; Walter, 1991; Yalom, 2008).

There are concerns that specialist palliative care providers have become entrenched in a medical model of care, losing the whole person holistic care element as the original hospice and palliative care movements intended (Clark, 2002; Lilley & Reid, 2024; Mount, 1976, Noonan, 2018).

“Death & dying are social issues and at the moment we are trying to solve them with a medical lens and that is what needs to change” (Libby Sallnow, The Lancet, 2022, 3:50).

Zooming in

Zooming in invites us to consider access to palliative care on a micro level. It is about challenging those people in policy making roles such as local and national government, health boards, hospitals, hospices, and other specialised health professional roles to think outside of a services based approach grounded on medical models, to a community approach founded on raising social capital (Abel & Kellehear, 2022).

Te Whatu Ora (2024) states it is “everyone’s responsibility” to provide palliative care, that two out of three people experience ‘normal dying’ requiring only their usual primary care team, and one out of three will experience ‘complex dying’ which will require specialist services such as those found in hospitals and hospices (6:11).

This is in line with the Compassionate Communities movement delivered as part of a Public Health approach to Palliative Care (Abel & Kellehear, 2022), where EOLD have an important role to play in encouraging social change, educating and building death and grief literacy in our communities (Noonan, 2018; Noonan et al., 2024).

“Death is certainly more of a stranger in the 21st century than it has been at any other time in the past” (Barbato, 2025, p. 3).

5 Common Barriers

From a compassionate communities perspective, it could be argued that the requirement for social change is one of the biggest existing barriers to accessing EOLD and the palliative approach to care that EOLD provide. This section focuses on five common themes occurring across literature that also make accessing EOLD’s a challenge for those who would benefit from their support (Collins et al., 2024; Krawczyk, 2024; Rawlings et al., 2018 Rawlings et al., 2020).

1. Lack of understanding of the role

The role of the end of life doula and the value they bring is not widely recognised by general public nor health care providers, scope of practice is variable between doula’s, making it difficult to articulate and inconsistent across providers.

2. Funding

As EOLD’s are not professionally recognised, they are not easily accessed through the healthcare system. People are either resistant, or financially unable, to pay for EOLD support. EOLD’s set their own charges which can vary depending on experience and geographical location. Not fully understanding the role of the EOLD can influence perceived value and benefits.

3. Relationships with health services

There is much to do in this space with regards to educating health services that EOLD’s are not wanting to take over from other services, but simply to fill in the gaps, and provide consistency in ways that other services cannot due to funding or restricted scope of practice. Health providers may feel threatened by another player competing for limited funding. Medicalising and professionalising primary palliative care makes it hard for people to access something that should be considered just good care.

4. Training, qualifications, and governing bodies

Lack of a regulating body means EOLD’s are not recognised or supported within healthcare. The cost of training and investing in personal development and growth as an EOLD is high and time consuming. It is a heavy financial and emotional commitment that not everyone is able to afford. There has been an emergence of high quality professional training, as well as professional governing bodies globally such as End of Life Doula Alliance Aotearoa (ELDAA) and Holistic End of Life Death Care Australia (HELD) working to promote credibility within general population and health care.

5. Demand for services

Challenges within community where identifying, asking for, offering and accepting help can be a minefield for many people, for many reasons (Grindrod et al., 2016). Challenges for people who are ageing, frail and dwindling include not recognising dying, leaving conversations too late or not having them at all. Transition points in illness trajectory are hard to recognise when there is fear and a denial of death, resulting in delayed access to support that could of made a difference (Abel et al., 2011).

“There is an urgent need for comprehensive evaluation of care across the healthcare system and targeted redesign of existing EOL care pathways to ensure that care aligns with what patients and informal caregivers consider high-quality patient-centred care at the EOL.” (Motamedi et.al., 2021).

Death Systems

Every society has a death system. These systems have evolved as a way to explain and make meaning of how societies respond to death (Noonan, 2018). Corr et al., (2013) introduce a model that illustrates how encounters with death, attitudes towards death and death-related practices influence each other to inform our experiences of death.

A death system includes hospitals, health care systems, emergency response organisations, professional care and industry such as funeral directors, grief counsellors, psychologists, as well as factoring in how community supports its affected citizens (Corr et al., 2013; Abel & Kellehear, 2022; Noonan, 2018).

“Death is now harder to predict, more difficult to manage, the source of more and more moral dilemmas and nasty choices, and spiritually more productive of anguish, ambivalence and uncertainty” (Callahan, 1993, p. 33).

Factors that influence our Death Systems

Circles of Care

The circles of care model (Abel, 2022) is used here to illustrate how each sphere influences or informs every part of society and our experience of end of life. Policy, as discussed previously, includes not only national policy, but also international policy What is happening in other countries informs and influences society on every level.

The compassionate communities approach supports patient and carer, inner and outer networks to influence the outer circles (community, service delivery and policy).

“…there is no funding in the future that is going to keep up with the death rate in front of us, the answer lies with the community…” (Hera Pierce, in Te Whatu Ora, 2024, 45:00).

Circles of Care

Conclusion

To implement the social change required to improve access to EOLD will take some time. Knowing that helps EOLD to keep advocating and raising awareness, to keep being the drip in the pond, one conversation at a time. At some point EOLD will be heard, there will be a ‘tipping point’ (Gladwell, 2002), experiencing a moment in time where this social movement crosses a threshold and results in change that becomes embodied in our social being.

It is a chicken and egg scenario where there is a workforce training and up-skilling for a role that does not yet have recognition or high demand. There has been no research in New Zealand, and limited research internationally, on the role of EOLD, likely due to said lack of recognition, resulting in limited opportunities to capture and research the experiences.

The challenge EOLD face is to continuously move towards this vision, given that governments change and societies are impacted by both national and international events. The good news is that even with the limited research available to us, EOLD communities in Aotearoa New Zealand, Australia, Canada, the UK & USA have grown considerably thanks to well-designed promotion, education and advocacy from a growing movement of supporters such as those whom have been cited in this work, along with the inception of organisations around the world to ensure the integrity and ethical practice of EOLD such as ELDAA, HELD, and others in the USA, Canada and UK.

One thing that feels true regardless of what is happening and influencing our behaviour is that we all want to be seen and heard, and to know that we mattered at the end of our lives. This can only happen on the large scale that is currently already being experienced, with demand only set to increase, by supporting our communities to find their way in bringing dying, caregiving and grief back to a social model of care...

References

Abel, J., Bowra, J., Walter, T., & Howarth, G. (2011). Compassionate community networks: supporting home dying. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 1(2), 129. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2011-000068.

Abel, J. (2022). Health and wellbeing. In J. Abel & A. Kellehear (Eds.), Oxford textbook of public health palliative care (pp. 64-72). Oxford University Press.

Abel, J., & Kellehear, A. (2022). Oxford textbook of public health palliative care. Oxford University Press.

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. (2018). National Palliative Care Strategy 2018. Australian Government Department of Health. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/national-palliative-care-strategy.

Barbato, M. (2025). Caring for the living and the dying (3rd ed.). Griffin Press.

Byock, I. (2025). A strategic path forward for hospice and palliative care: A white paper on the potential future of the field [White paper]. Palliative Medicine Reports 6:1, pp. 308–323. http://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2025.0030.

Callahan, D. (1993). Pursuing a peaceful death. Hastings Center Report, 23(4), 33-38.

Clark, D. (2002). Between hope and acceptance: The medicalisation of dying. British Medical Journal, 324(7342), 905. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7342.905.

Collins, E. F., Galloway-Salazar, Q., Johnson, E., Blechman, J., Rush, M., Clare, E., Johnson, A., Sethi, A., Rosa, W. E., & Izumi, S. (2025). Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about End-of-Life Doulas. Journal of palliative medicine, 28(6), 808–814. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2024.0261.

Corr, C.A., Corr, D.M., & Doka, K.J. (2013). Death & dying, life & living (8th ed.). Cengage.

Doughty, C. (2017). From here to eternity: Travelling the world to find the good death. Orion Books.

Gladwell, M. (2002). The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference. Back Bay Books.

Grindrod, A., & Rumbold, B. (2016). Healthy End of Life Program (HELP): Offering, asking for and accepting help. Creating an End of Life Collaborative Community Culture. La Trobe University Public Health Palliative Care Unit, Melbourne, Australia. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309558092.

Health Canada. (2023). The framework on palliative care in Canada - five years later: A report on the state of palliative care in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/health-system-services/framework-palliative-care-five-years-later.html.

Kellehear, A. (2007). A social history of dying [Kindle edition]. Cambridge Press.

Krawczyk, M. (2024). Death doula’s could lead end of life care. British Medical Journal, 387. http://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.q2853.

Lewis, J.M., DiGiacomo, M., Currow, D.C., & Davidson, P.M. (2011). Dying in the margins: understanding palliative care and socioeconomic deprivation in the developed world. Journal of pain and symptom management, 42(1), 105-118.

Lilley, D., & Reid, K. (2024). Exploring palliative care debates: Equitable access and the role of social workers. Aotearoa New Zealand Journal of Social Issues 36(4), 97-108. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol36iss4id1170.

Lines-MacKenzie, J. (2025, February 11). Palliative care likely suffer proposed job cuts. Waikato Times. https://www.waikatotimes.co.nz/nz-news/360575129/palliative-care-likely-suffer-proposed-job-cuts.

McLeod H. (2016). The need for palliative care in New Zealand: A technical report prepared by Heather McLeod for the Ministry of Health. Ministry of Health.

McLeod, H., & Atkinson, J. (2019a). Policy Brief on Health System Costing in the Last Years of Life in New Zealand. Ministry of Health.

McLeod, H., & Atkinson, J. (2019b). Policy Brief on Place of Care and Time in the Community at the End of Life in New Zealand. Ministry of Health.

McLeod, H., & Atkinson, J. (2019c). Policy Brief on Trajectories of Care at the End of Life in New Zealand. Ministry of Health.

Motamedi, M., Clark, J., Brandenburg, C., Bakhit, M., Michaleff Z. A., Ooi, M., Bahudin, D., Ní Chróinín, D., Albarqouni, L., and Cardona, M. (2021). Concerns and potential improvements in end-of-life care from the perspectives of older patients and informal caregivers: a scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 729.

Mount, B.M. (1976). The problem of caring for the dying in a general hospital; the palliative care unit as a possible solution. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 115(2), 119.

Natural Grace Holistic Funeral Care. (n.d.). Ten stages of living [Webpage]. https://naturalgrace.com.au/macedon-ranges/faqs/.

Noonan, K. (2018). Renegade stories: A study of deathworkers using social approaches to dying, death and loss in Australia[Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Western Sydney University.

Noonan, K., Grindrod, A., Shrestha, S., Lee, S., Leonard, R., & Johansson, T. (2024). Progressing the Death Literacy Index: the development of a revised version (DLI-R) and a short format (DLI-9). Palliative Care and Social Practice, 18. http://doi.org/10.1177/26323524241274806.

Pae Ora (Healthy Futures) Act 2022. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2022/0030/latest/lms575405.html.

Phillips, J.L., Elvidge, N., & Currow, D. (2024). Challenges and future directions of palliative care globally. In R.D. MacLeod & L. Van den Block (eds) Textbook of palliative care (2nd ed., pp. 121-141). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31738-0_5-2.

Rawlings, D., Tieman, J., Miller-Lewis, L., Swetenham, K. (2019). What role do Death Doulas play in end-of-life care? A systematic review. Health and Social Care Community, 2019(27). e82-e94. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12660.

Rawlings, D., Litster, C., Miller-Lewis, L., Tieman, J., & Swetenham, K. (2020). A qualitative analysis of interviews with Australian and International death doulas on their role. Health and Social Care Community, 2020(29). https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13120.

Richards, N. (2022). The equity turn in palliative and end of life care research: Lessons from the poverty literature. Sociology Compass, 16(5), Article e12969. https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12969.

Te Whatu Ora. (2023, May 23). Planning for palliative care services in Aotearoa hui [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/829578999/44ac9fa03c.

Te Whatu Ora. (2024, October 23). Health NZ palliative care work programme: Adult models of care working group update[Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/1026311946/7df03b2338?share=copy.

The Lancet (2022, February 1). A new vision for death and dying: The Lancet Commission on the value of death [Video]. https://youtu.be/dRqjkIPMBhw?si=aN9f64BDdvgFN63h.

The Treasury. (2021). Statement on the long term fiscal position: He Tirohanga Mokopuna 2021. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-09/ltfs-2021_2.pdf.

Whitelaw, S., Bell, A., & Clark, D. (2022). The expression of ‘policy’ in palliative care: A critical review. Health policy, 126(9), 889-898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.06.010.

Walter, T. (1991). Modern death: Taboo or not taboo?. Sociology, 25(2), 293-310.

World Health Organisation. (2020). Palliative care. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care.

Yalom, I. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the dread of death. Piatkus Books.